Guide

Why We Pretend to Like Important Albums

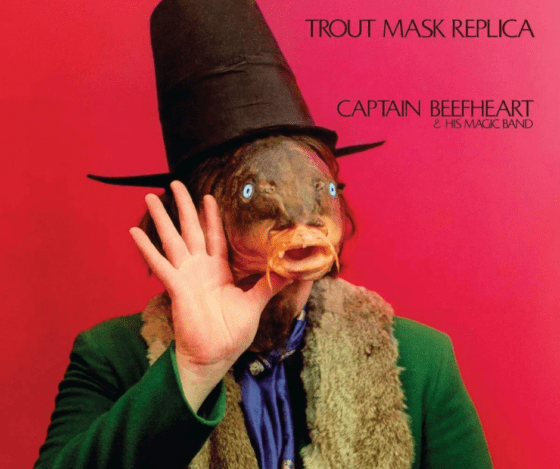

We’ve all been there. You’re at a dinner party, and someone brings up Captain Beefheart’s “Trout Mask Replica”. Heads nod, someone calls it “ahead of its time,” and before you know it, you’re chiming in with the same kind of praise. Deep down, though? You remember the last time you actually tried to listen four minutes of what sounded like a washing machine tumbling down a flight of stairs before you gave up and put on something more forgiving.

That kind of pretending isn’t cruel or fake in a malicious sense. It’s part of being human. We say we “love” these records because they signal something bigger than the music itself: taste, intellect, belonging. But the tension between what we claim and what we actually enjoy says a lot about culture, community, and why so many of us end up playing this exhausting game of musical theater.

The psychology of musical pretending (Why We Pretend to Like Important Albums)

It’s tempting to think this is just about social climbing, trying to look smart or cool. But the roots go deeper. Psychologists Peter Rentfrow and Samuel Gosling found that music preferences act like identity badges. Saying you love a certain album isn’t only about sound waves; it’s shorthand for “this is who I am, this is the tribe I belong to.”

That’s where social signaling kicks in. Humans are wired to crave acceptance and dodge rejection, especially in our teens when everything feels high-stakes. In those years, approval from friends lights up the brain like fireworks. If knowing the right obscure band name or pretending to appreciate the “important” record keeps you in the circle, you’ll do it. Survival by playlist.

Pierre Bourdieu’s idea of cultural capital takes it further: obscure or difficult music becomes a kind of currency. Owning knowledge of it buys you entry into certain groups. The rarer and harder the music is, the more powerful that signal becomes.

The irony? The whole system rewards performance more than actual feeling. Data from streaming platforms makes this painfully clear. People praise experimental albums online but rarely make it through them in private. So the canon of “great” records often functions more like a social test than a source of pleasure.

How critics turn albums into monuments (Why We Pretend to Like Important Albums)

Critics have always had outsized influence on what counts as “essential.” Take The Velvet Underground: their debut sold only about 10,000 copies at first, yet today it’s everywhere on best-of lists. Big Star’s “Third/Sister Lovers” bombed commercially, but critics later crowned it an alt-rock masterpiece. Or Television’s “Marquee Moon”, which originally flopped but got framed as groundbreaking.

The pattern is familiar: poor sales, followed by critical rescue, equals canonization. Critics don’t just review records; they build narratives. Rolling Stone’s “500 Greatest Albums” functions like scripture. A perfect 10 from Pitchfork can elevate an album more than any radio campaign. Universities then teach these records as gospel, reinforcing the hierarchy.

The issue isn’t that critics elevate overlooked work, that can be great. The issue is how those decisions spill out into wider culture. Once a record is labeled “important,” not loving it starts to feel like a personal failing. Admitting you can’t get into “Kid A” or that “Metal Machine Music” sounds like punishment becomes more than a taste opinion, it’s almost a confession of ignorance.

Even critics admit the pressure. Kelefa Sanneh once wrote about how rock criticism developed like a grading system for culture, handing out A’s and F’s as though taste was objective. Former Pitchfork writers have described how much their reviews were shaped by editorial agendas, not just raw feeling.

Gatekeepers and their unwritten rules (Why We Pretend to Like Important Albums)

Every music scene has its lines in the sand. Metal fans guard against bands that “sell out.” Hip hop communities argue endlessly about authenticity. Electronic fans debate “real” underground clubs versus mainstream festivals. Indie kids cling to obscurity, turning “you’ve probably never heard of them” into a point of pride.

These gatekeeping rituals serve a purpose. They build identity, protect tradition, and sometimes keep quality high. But they also create exhausting environments where every choice gets policed. You’re either “real” or you’re an outsider.

That’s where guilty pleasures creep in. Studies show around 90 percent of people listen to music they’d never admit to, with most saving those tracks for private listening. And it’s telling that pop songs, boy bands, and women-led pop acts make up most of that category. The sexism is obvious. Challenging experimental music by men gets respect, while equally inventive pop by women often gets written off as shallow or fake.

One Direction fans, for example, often report being mocked not just by peers but by family. And entire fanbases get dismissed simply because they’re young and female. The same scenes that celebrate Beefheart’s chaos will sneer at Britney Spears’s risks.

Social media and the performance of taste (Why We Pretend to Like Important Albums)

Digital platforms promised to level the playing field, but they mostly just shifted the rules. Streaming services offer endless discovery on the surface, but their algorithms tend to trap people in loops of familiar sounds. Spotify, for instance, has made even record executives worry about intros that last longer than 20 seconds, since the data shows listeners skip quickly.

Social media then adds another layer. Instagram Stories let us broadcast what we’re listening to, even if it’s not really our daily soundtrack. TikTok rewards jumping on trending audio, whether you like the song or not. Twitter (or X, if you insist) thrives on hot takes and cultural one-liners. All of it turns taste into a kind of performance.

Playlists have become the new cultural battlefield. Anyone can be a curator, but the competition for followers creates another hierarchy. People build careers on being tastemakers, while privately listening to something entirely different. Researchers call it “context-aware listening,” and it basically means we present one musical identity in public and keep another for ourselves.

The streaming data tells a different story (Why We Pretend to Like Important Albums)

For all the critical worship of certain “important” albums, the actual data tells a harsher truth. Skip rates are high on difficult records. Completion percentages are low. People who swear they love avant-garde albums usually spend most of their listening hours on accessible and familiar tracks.

Streaming has also changed how songs are written. Long intros, once a hallmark of artistic patience, are now considered a risk. If you don’t hook the listener fast, the platform’s metrics punish you. This collides directly with the critic-driven narrative of “serious listening” that takes time and effort.

And while digital distribution supposedly opened the gates, new forms of gatekeeping replaced the old ones. Algorithmic visibility is everything. Success now depends less on radio DJs and more on understanding how to game playlists, analytics, and algorithms. The cultural hierarchy survived, just with new gatekeepers in charge.

Why we keep doing this to ourselves (Why We Pretend to Like Important Albums)

If this cycle is so tiring, why do we keep playing along? Because it serves real social functions. Pretending sophistication can get you into circles you want to be part of. It helps build identity. Sometimes it even leads you to music you might never have discovered otherwise. And occasionally, forcing yourself through a difficult album does open up new ways of hearing.

The problem isn’t the aspiration itself. It’s when the performance completely detaches from actual enjoyment. When the goal becomes looking cultured instead of feeling something real. Then we end up with a culture that values the right references more than honest connection.

There’s some hope that younger listeners are moving away from this. Data-heavy platforms make it harder to maintain false taste profiles, and younger generations place a higher value on authenticity. But the urge to signal still finds new outlets, whether it’s playlists, memes, or niche micro-scenes.

Finding a way forward (Why We Pretend to Like Important Albums)

Maybe the answer isn’t to stop aspiring altogether but to separate performance from experience. We can respect the canon without pretending those albums are on heavy rotation at home. We can admire experimental work without lying about whether it moves us.

The hardest part of pretension is the energy it takes to keep it going. Monitoring what we say, curating what we share, feigning enthusiasm none of that leaves much room for actual discovery. When we let go of the pressure, we usually stumble into the music that truly resonates, even if it doesn’t score cultural points.

Music is most powerful when it reflects our real lives, not the image we’re trying to sell. The albums that stick aren’t always the ones on greatest-of-all-time lists, but the ones that connect with our own moments and feelings.

The point isn’t to have perfect taste. It’s to have honest encounters with sound, whatever shape they take. Sometimes that will mean “important” albums, and sometimes it won’t. Both are fine, as long as we’re being real about it.

Sources For Why We Pretend to Like Important Albums

- The Structure of Musical Preferences: A Five-Factor Model – PMC

- The Structure and Personality Correlates of Music Preferences – University of Texas

- Musical taste, in-group favoritism, and social identity theory – ResearchGate

- The role of music in adolescent development – Taylor & Francis Online

- The Psychology of Taste: The Intertwining of Music and Identity – The Science Survey

- The Power of Peers – NIH News in Health

- Changing Highbrow Taste: From Snob to Omnivore – Semantic Scholar

- The social positions of taste between and within music genres – Sage Journals

- Cultural Capital Theory of Pierre Bourdieu – Simply Psychology

- Cultural capital – Wikipedia

- AlgoRhythm: How Spotify Standardizes Listening – The Decision Lab

- Algorithmic Effects on the Diversity of Consumption on Spotify – Spotify Research

- Streaming’s Effects on Music Culture – Sage Journals

- The relation of culture, socio-economics, and friendship to music preferences – PMC

- Counterbalance: Big Star’s ‘Third/Sister Lovers’ – PopMatters

- Third/Sister Lovers – Rock Music Wiki

- The Big Star masterpiece that disappeared for decades – Far Out Magazine

- Everything In Its Right Place: How a Perfect 10.0 Review of Radiohead’s ‘Kid A’ Changed Music Criticism – Billboard

- Critiquing the Canon: The Role of Criticism in Canon Formation – Cambridge Core

- Critiquing the Canon: The Role of Criticism in Canon Formation – Open University

- Kid A – Wikipedia

- Social Signaling Through Taste in Aesthetics – Medium

- Kelefa Sanneh discusses his article ‘How Music Criticism Lost Its Edge’ – NPR

- Pouring One Out for Pitchfork – Rolling Stone

- Gatekeeping Music Never Made Sense – Vocal Media

- Gatekeepers and elitists are ruining music – The Hofstra Chronicle

- Maybe you’re a snob? A Look Into Elitism in Music – Craccum

- The pretentious gatekeeping around Sleep Token – Louder

- The infamous phenomenon of gatekeeping music – The Post

- Gatekeeping in Music: Good or Bad? – Medium

- The Unbecoming Phenomenon That Is Gatekeeping Music – Medium

- Gatekeeping Music: is It Toxic for the Music Industry? – The Teen Magazine

- A matter of space: how nightlife communities fight gatekeeping – Electronic Beats

- Not Metal Enough – A Psychological Perspective on Gatekeeping – Loudwire

- “Guilty Pleasure” Music is just Another Way to Shame Women – Fourteen East

- What Is a Guilty Pleasure Song? – Aura Health

- Social Network Profiles as Taste Performances – Oxford Academic

- Impression management through social media – Emerald Insight

- Liking as taste making: Social media practices – Sage Journals

- Impression management – Wikipedia

- Safety and Privacy center – Spotify

- The Awkward Truth Behind Skip Rates – Hypebot

- In a world of ‘algorithmic culture,’ music critics fight for relevance – Columbia Journalism Review

- The Impact of Streaming Platforms on the Music Industry – Illustrate Magazine

- Effects of algorithmic curation in users’ music taste on Spotify – ResearchGate

- One More Turn after the Algorithmic Turn? Spotify’s Colonization – Taylor & Francis

- Streaming’s Effects on Music Culture: Old Anxieties and New Simplifications – ResearchGate

- Impression Management Theory – Fiveable

- Toward understanding the functions of peer influence – PMC

- Subcultural escapades via music consumption – ScienceDirect

- Captain Beefheart & His Magic Band – Trout Mask Replica review – Album of The Year

- How to break free of Spotify’s algorithm – MIT Technology Review

- The Worst Songs We Love So Much – Defector

- Social Media Allows Users To Make Their Music Taste a Personality Trait – Study Breaks

- Cultural Familiarity and Individual Musical Taste Differently Affect Social Bonding – Nature

- From the functions of music to music preference – ResearchGate

- Streets of Minneapolis Review | Bruce Springsteen | Single Review | 4/5 - January 30, 2026

- How Did I Get Here? Review – Louis Tomlinson – Album Review - January 23, 2026

- Wall of Sound Review | Charli xcx | Single Review | 4/5 - January 21, 2026